The famous, fad herb, Echinacea purpurea, overtook the world probably as a result of an error. It’s sibling, Echinacea angustifolia, was the one with the more extensive history of traditional use in its home of North America, but apparently someone sent the wrong seeds to Germany. That’s why the lesser used herb, E. purpurea became more intensely studied, widely encapsulated, and all the rage for the previous few decades. Unfortunately, E. angustifolia is smaller and harder to grow, plus you have to wait 3 or 4 years to harvest the roots of this plant. That’s another reason for its larger relative to have become more popular. Most significantly, E. Angustifolia has become overharvested, more rare, and more expensive, as is a third useful species, E. pallida.

If you would like not to wait so long for your roots, or wish to allow the more rare Echinacea species to recover, you could utilize the very weed-like Rudbeckia hirta, or Black Eyed Susan, another North American native of USDA hardiness zones 3-9. This plant has a similar traditional history of use, by the very first U.S. immigrants, and for a similar array of illnesses as those which are addressed with Echinacea. While it has less formal research to bolster these applications, more information is slowly accumulating, and revealing constituents and activities which could account for the use and observed efficacy. Black eyed Susan is a much faster growing and especially faster spreading, short lived perennial weed which can supply plenty of material for medicinal use. Since conservation minded people have been calling for a reduction in the use of E. angustifolia most particularly, you could consider adopting the drought tolerant and prolific black eyed Susan.

The three species used by America’s first immigrants are Rudbeckia hirta, black eyed Susan, R. Laciniata, cutleaf coneflower, and R. fulgida, orange coneflower. R. hirta is a smaller plant, most widely distributed throughout the continent, and so this article will concentrate on that species. There is large overlap of the traditional uses of these 3 species, however. R. fulgida is more easily confused with R. hirta, because they are similar in size. But R. hirta is hairier and it lacks the stolons (above ground rooting stems) of R. fulgida, which allow that plant to spread quickly over the ground. R. hirta relies on seeds for its rapid spread. R. laciniata is a much larger plant with highly variable, pinnately divided leaves. It inhabits wetter areas around waterways and can grow to 10 feet (3 meters) tall.

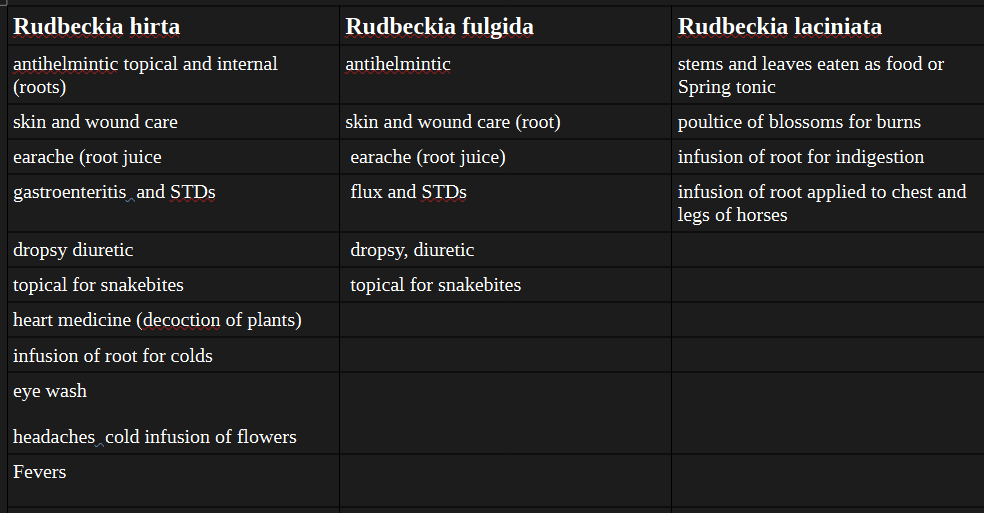

Traditional uses of Rudbeckia species by America’s first immigrants were compiled from the Native American Ethnobotany Database, and summarized below. Use for snakebite, infections, fevers, colds, overlaps with the applications of Echinacea.

At weedom, there is plenty of black eyed Susan, R. hirta, the most widespread of the genus. From a couple of plants that we obtained from one of our farmer’s market buddies, it has done it’s weed thing, and now occupies numerous spots west of our abode. No drought, nor abuse, nor lawnmower could stop this weed, and we’re happy with that. Like the dandelions, this plant seems to learn how to bloom low when it’s been mowed. It has vastly outpaced our Echinacea, and we have enough to give plants away. In the latter half of the summer, it fills the gardens with blooms which continue until frost arrives.

New plants start out in either the Fall or the Spring as a rosette of green elliptical leaves. These leaves grow up to 3 -6 inches (7-15 cm.) in length and perhaps up to 2 inches (5 cm.) wide. The leaves are covered, above and below with copious coarse hairs, which are rough to the touch. They wouldn’t be fun to eat from a texture standpoint, and the taste is not tempting. Leaves have palmate venation, irregular teeth, and sometimes the larger leaves develop lobes. Hairy and winged petioles connect the leaves to the base of the rosette.

In June, stems emerge from these rosettes, often in the second year, becoming branched and bearing numerous blooms. Everyone has a different story about the longevity of this perennial weed, which often stays green throughout milder winters, or can die back to the ground under more severe circumstances, and reemerge in spring. Some report that it behaves as an annual in more extreme hot or cold regions of its range. We have seen rosettes spread wider into clusters in subsequent years, putting up multiple flowering stems. Our hairy weeds do not spread by stolons so we know that we’re looking at R. hirta rather than fulgida. As members of the family Asteraceae, plants of the genus Rudbeckia produce compound blooms, singly at the top of a stem or branch of the flowering stem.

Daisylike blooms, reaching 1-3 inches (3-8cm.) in diameter, begin with up to 20 sterile ray florets gradually extending from a central brown circle of 50-300 disk florets. Each of these central florets has 5 anthers arranged in tubular fashion around a single pistil. This disk of florets gradually bulges in the center until it becomes more and more conical as the flowers mature and elongate. Ray flowers can be a golden yellow to orange, and there are some cultivars of R. hirta which assume reddish tones. But above is the wild color that we see on roadsides and open areas throughout our region in hardiness zone 6 of flyover U.S.A. The ray flowers have a band of U.V. absorbing color, closest to the disc florets, which bees can see, that helps them to distinguish this species from others. We can observe a darker golden shade on the inner two thirds, and a more yellow shade on the outermost third of the ray flowers.

The tiny seeds of Rudbeckia hirta are four sided, wingless, and each composite bloom is capable of producing up to a few hundred. They’re regarded as anywhere from poisonous to merely inedible depending upon who is pondering the issue. The entire plant is credited with being poisonous to cats. Ours are not at all tempted.

What little information on the constituents of Rudbeckia species dribbles in is nothing like massive controlled trials (which will never happen for these unpatentable herbal drugs). However it does seem supportive of the traditional uses of the herbs. There is good in-vitro inhibition of pseudomonas aeruginosa in isolates of the plant material, and even better inhibition of Candida albicans, that is comparable to fluconazole. This ability to inhibit gram negative bacteria and fungal infections backs up the wound care uses and applications for ear and other infections.

Anti-oxidant activity has been demonstrated in vitro, as has been various demonstrations of the anti-inflammatory activity. including inibition of 5-lipooxygenase, an enzyme that catalyzes a metabolic pathway from arachadonic acid that yields an array of leukotrienes, which mediate inflammation in the body. Mechanistically, this points to very strong anti-inflammatory activity provided by methanol extracted fractions from the flowers of Rudbeckia hirta. Additionally this fraction contains compounds which inhibit haemagglutinin stimulated lymphocyte proliferation. Therefore these plants, with their complex actions, are much more accurately described as immune modulators rather than immune stimulants.

Patulitrin, a flavonoid component of R. hirta, has activity in lowering blood pressure, elicits anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting 5-lipooxygenase, inhibits histamine, and has antimicrobial properties. Rudbeckolide, a recently isolated terpenoid lactone also exhibits strong activity against 5-lipooxygenase.

The mechanism of both Echinacea and Rudbeckia for alleviating snakebite is thought to be through inhibiting the hyaluronidase component of snake venom which degrades the “glue”, containing hyaluronic acid, that holds bodily tissues together. Hyaluronidase inhibitors are widespread among plants.

Hyaluronidase serves to spread whatever other components might be present in the venom throughout the body of the prey. So the plant components, which inhibit this enzyme, tend to preserve the tissue from further damage, as well as reducing the spread of any other toxins. Dr. Patrick Jones, DVM, currently touts this application for both the Echinacea spp. and Rudbeckia hirta plants is naturopathic herbalist who practices in the western state of Idaho. Since poisonous snakes are very rare in the region of weedom, I claim no such experience. Dr. Jones, on the other hand uses the roots of these herbs for snakebites, (of the pit viper, e.g. rattlesnake type) for hobo spider bites and for brown recluse bites, and reports success with both his veterinary patients and human clients. (For other uses, he tends to favor using the young flowers since they are easier to collect than the roots, and perform suitably. Don’t wait till seeds start forming.)

Another western U.S. herbalist who used Rudbeckia interchangeably is Michael Moore, who founded the SouthWestern School of Herbal Medicine. He utilized them as diuretics and weak cardiac stimulants, and wrote that either root tincture of Rudbeckia laciniata or teaspoon doses of the aqueous infusion of aerial parts of R. hirta be used for this application. He found these herbs to have more warming effects than Echinacea, and to not need the addition of stimulatory herbs to assist in their functions.

Some final notes, R. hirta is generally more potent than Echinacea for overlapping purposes. (Echinacea is an herb which requires larger doses than most other herbs in order to work, which is why many people have experienced disappointment with it.) Pregnant ladies should avoid R. hirta.

Here at weedom, we have plenty of Black eyed Susan to harvest, and almost enough Echinacea after numerous years :-D, and are looking forward to some tincture and tea making very soon. We welcome comments and questions, and for you to weigh in on how you’ve been experiencing these excellent weeds.

Thanks so much for this, I have been looking for good information on Black eyed Susan for ages and yours is the first comprehensive article I have found. Where I live in Ireland echinacea is hard to grow but this beautiful plant flourishes well. Every herbalist needs to be far more committed to sustainability and making use of plants which grow locally, so I appreciate this post

I had no idea black eyed Susan had medicinal uses! Mine are happily spreading after much coaxing on my part for a couple of years.