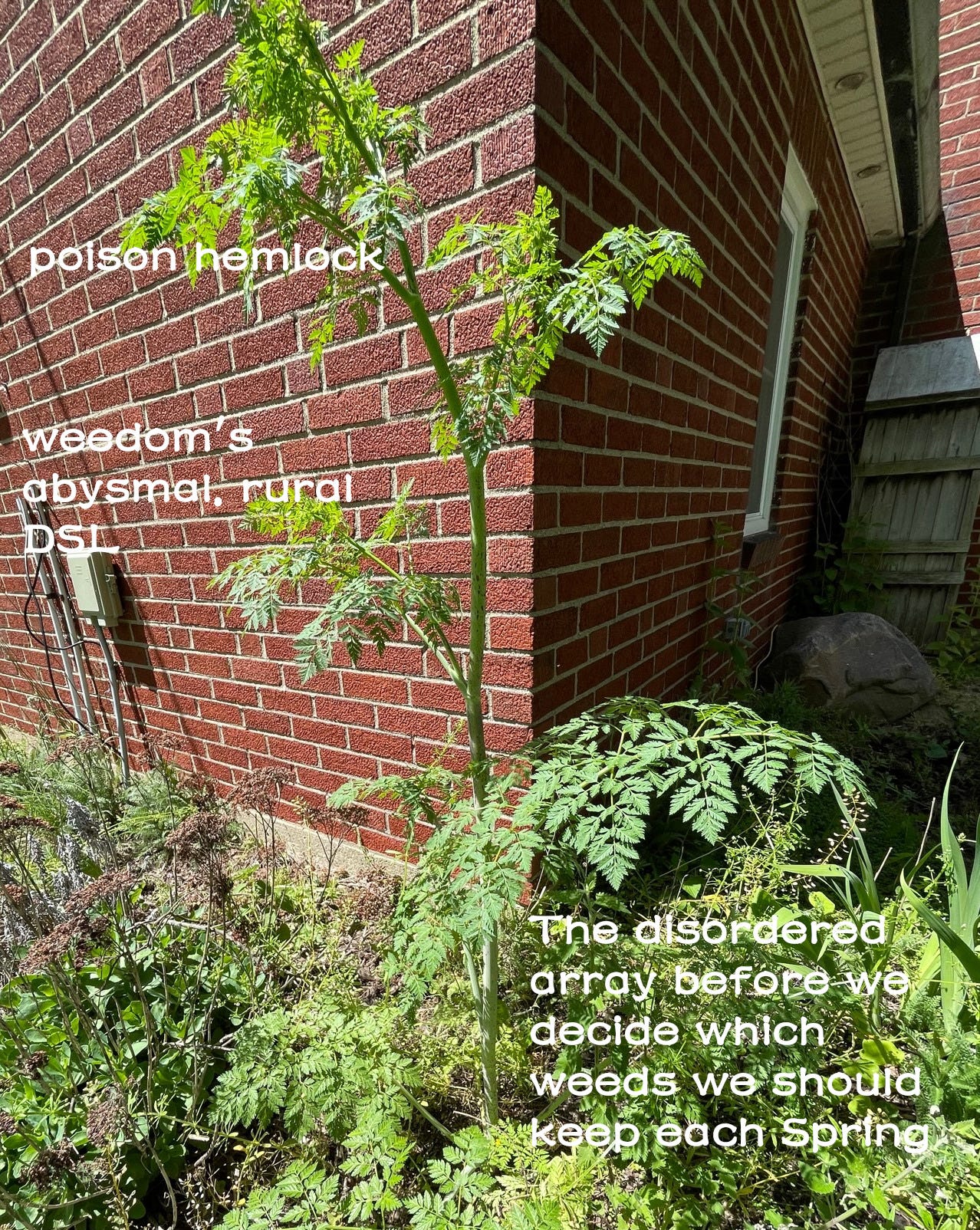

It’s getting busy at weedom with the warm weather, but we won’t abandon you. It’s light writing and reading time, this week, which means no “Where we dig” section. Instead, there will be a little tour of a very poisonous weed that we are not using, and that you might not want close to your living areas, or pets or any livestock that are new to the area. (A lot of herd type animals get smart about the toxic weeds.)

In December there was a distinctive little weed growing in the landscape. This photo was taken on the fly. Normally we get rid of those things. Since the newsletter of weedom was being gestated, we preserved this little gem hoping for some later pictures.

Conium maculatum, a member of Apiaceae, the carrot family, is a biennial weed which is distinctive for doubly compound leaves, which are very symmetrical and pinnately arranged all the way. Many of the lookalikes lack this much symmetry in the leaf arrangement. Also, many of the lookalikes have some hairs, while this special do-not-eat is hairless, a.k.a. glabrous. In the second year, a thick round, hollow, juicy looking stem emerges from the rosette, which is green at first, then gains a coppery tinge with purple spots, which accounts for the ‘maculatum’ species name. You don’t want any part of that stem juice. In fact we don’t recommend any plant parts at all.

Above is our mostly grown poison hemlock which did not reach a normal full size because this spring is dry, and our drainage system doesn’t allow much water retention around the house. Some catnip was growing right next to this noxious plant. Of course Renob of weedom found that catnip and was sniffing at it, so we shooed him away, ripped the catnip out and got rid of it. He’s not interested in that area anymore. Fortunately, this is a good year for poison hemlock, and some impressive specimens made themselves readily available along the perimeter of the farm. Some of these had stems close to an inch and a half in diameter. Each plant can be 6 or more feet high and 5 feet wide when full grown. Flowers form an umbel, similar to Queen Anne’s lace. In the case of poison hemlock, the flower groups of each umbel are more more divided, whereas the Queen Anne’s lace umbels are more continuous appearing when looking from the top, and the stems of that plant are not as large, fleshy, spotted as those of poison hemlock. Queen Anne’s lace blooms later and the plant smells better, more carroty.

The best way to learn the leaves and flowers is a close up. You really want to get to know this weed, so you don’t mistake it for Angelica species, parsnips, parsley, Spanish needles, or Queen Anne’s lace at any stage of development. Remember, poison hemlock is hairless, and it’s pretty stinky. Once you get used to seeing the baby plants around where the tall ones grow, you’ll recognize it anywhere.

By now, you’d find the poison hemlock anywhere. The main thing to do is to learn those first year rosettes, such as seen at the top. So study the baby plants that arise around the tall plants. Once you learn those leaf patterns and the hairless ribbed stems, you’ll be a long way towards never mistaking this thing for an edible plant.

What makes this plant so very special are the alkaloids which bind to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, thereby causing muscular paralysis, and eventually respiratory collapse and death. Gamma coniciene, which is at highest levels in the Spring, is the precursor of coniine, N-methylconiine, pseudoconhydrine and conhydrine, all of which are piperidine alkaloids. Coniine, a bitter (like any alkaloid) oily substance that smells a bit like mouse urine, is structurally similar to nicotine. It takes about 100 mg. of this compound, or the amount in about 6 leaves to possibly cause death syndrome in a human. The compounds are more concentrated in the roots and seeds than they are in the leaves. Poisoning victims can become sleepy in about 30 minutes after ingesting the leaves, with death following a couple hours later. Supportive care and ventilation has been used to keep the victims alive for the 48 to 72 hours it takes for the poison to wear off, so there are expensive ICU medical bills facing any survivors. Legend has it that Socrates picked this method for his death penalty. He had been charged with ‘corrupting’ the youth in Athens, (by getting them to think??) way back, almost 400 years B.C.

Conium maculatum was used as a topical anesthetic, to treat tumors, as a muscle relaxant, but it’s very difficult to dose it without causing death syndrome. We consider hemlock herbalism to be like using curare or diprivan (remember Michael Jackson?) without benefit of having a ventilator or ICU around the house. In modern times you’ll see it used in homeopathic remedies for vertigo, tumors, pain, urinary problems, etc. These preparations are designed to be so extremely dilute that they fall far below the toxic dose.

An evergreen called a hemlock tree, Tsuga species, is not poisonous, but perhaps got its name due to smelling a little nasty like poison hemlock.

Water hemlock is severely poisonous plant of the Cicuta genus, in the same Apiaceae family, which contains cicutoxin, an antagonist of GABA receptors, that causes seizures and death. We might someday report on the Cicuta group of weeds if we spot any. Not counting on that during this dry year. This plant is a good reason to mow down the pasture weeds. If you cut them down before they go to seed, these weeds will eventually die out. Seeds seem to last around 5 or 6 years in the soil. We had a lot of them south of our mini-swamp, so we weed whacked them year after year, greatly reducing the population. You can tell when online articles are written by people who haven’t seen the weed. They tell you to get into a hazmat type clothing in the dead of summer, and eradicate the plants, including the roots, and gather them up in plastic bags to throw the toxic waste into the trash. That’s not sustainable. First of all, taking the root of the second year plant is a waste of time, and risks more topical exposure. The root will die soon, according to the plant’s lifecycle. The first year plant can grow back, but you can mow it again. If you have just a few plants, you could chop them. Wear gloves. Don’t get the juice all over your skin, or in your eyes, since extensive topical exposure can also be harmful. If you want to move weeds away from pets, hide them in an unused part of the property, and perhaps drop some trimmings of thorny plants such as roses, barberry, blackberry, etc on top of them as a pet deterrent. The toxins degrade naturally by environmental exposure, and composting doesn’t really speed this up, so there’s no benefit to the effort of grinding it into a compost pile. Do this the easiest way, so you get it done.

The days of the little poison hemlock in our landscape are numbered. It’s gotta go before it produces seed. That weed brought you this article, so it’s sort of a sad goodbye.

Bonus fun: At weedom it’s a huge year for poison ivy, which is Everywhere. Really obnoxious. On top, you see the classic 3 asymetric leaves of poison ivy , and just below it, 5 leaves of Virginia creeper.

Poison ivy, Toxicodendron radicans, is bad enough on your skin, due to the rash inducing oil called urushiol. A famous local herbalist was lost to lung injury due to burning poison ivy, so we know to keep it out of the burn pile. Virginia creeper, Parthenocissus quinquefolia is often confused with poison ivy, due to a similar sprouting and extensively vining growth habit, but is much less trouble in general. Raphides found in this plant can irritate the skin of some people. The berries of either of these two plants are not edible.

So much to plant and chop and fix. Gotta work! Want to see more poison plants detailed here? Which ones are you seeing? If you visit us in Notes, you can show pictures. Drop some comments! Then be sure to get outside and find some weeds.

Coincidentally, I just learned this one in a plant ID class, found seedlings in my yard this morning, and removed them. Love Virginia creeper, and we can’t eat the berries, but the birds do.