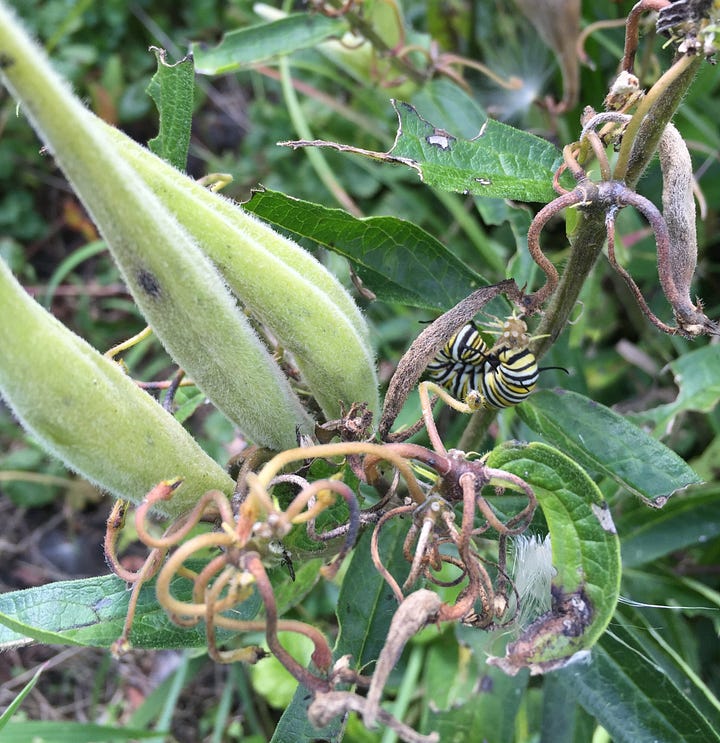

It seems that the whole world loves milkweeds now, because they’re butterfly food. The fastidious, (picky) caterpillars, the larvae of monarch butterflies, love this genus of weeds the most, perhaps exclusively. Milkweed tussock moth larvae also feed on these plants. At weedom (while we’re waiting for those goldenrods to bloom) we have a couple of common species of milkweeds to show you. Although Asclepias syriaca is one of the main weeds left standing in our drought conditions, there have been only a few monarchs dropping by to lay their eggs this spring and summer. We’ve had some pretty big monarch years, but 2023 isn’t one of them. Some other caterpillars and bugs are chowing through these weeds, and after reading this article, you might decide to defy the verdict of Euell Gibbons, who regarded this plant unpalatable. Most parts ARE edible, at some stage or other, but blanch it first. Milkweed puts out some tremendous, pleasantly scented flowers during a fairly long blooming season that runs from May until Autumn. These attract a wide variety of pollinators, beetles and butterflies.

A smaller crop of butterfly weeds, Asclepias tuberosa, regularly appear here, and one of them was sadly chopped when the hay was cut in our side yard. Another little clutch of them pops up in the garden year after year, and of course we leave it in place, because, well, it’s weedom. Numerous other species of milkweeds abound within U.S. hardiness zones 3-9, some of them liking dry conditions, and some preferring swampier areas. Check this Birds and Blooms site for a brief presentation of 10 of them.

Let’s nerd out on some botany to make sure that everyone outside of the monarch butterfly fan club gets to know the common milkweed. The family of milkweeds, Asclepiaceae has been adopted into the Apocynaceae, dogbane family, of about 400 genera including many productive and medicinal species worldwide, such as the classic Rauwolfia serpentina. Our Asclepias syriaca is a North American native that occupies mainly the eastern 2/3rds of the USA and southern parts of Canada. Leaves and the young stem have a rubbery appearance, and as expected, produce copious quantities of latex, a milky white sap when either are broken. Plants are seldom branched, and may exceed 1.7 meters (5 feet) in height, with the leaves reaching 20-25 cm (8-10 inches) in length. Young leaves at the growing tip of the plant can be hairy, particularly on the underside, and these hairs become less apparent as the leaf grows. Veins are pinnately arranged, with the central vein sometimes becoming purple above, and quite thick below. The leaf edge is entire, (no teeth). Very short, sturdy petioles attach the heavy leaves to the stem opposite one another, and each pair alternates 90 degrees with respect to the pair below. A broken milkweed stem shows a somewhat succulent character, but hollow center, and will produce abundant latex.

Scroll back up to see the flowers, which form umbels of up to 100 blooms, each on their own pedicel (flower stem). Each flower opens, with the five petals folding backwards, revealing a crown with 5 hooded structures surrounding the pistil in the center, which is fused with the male stamens into a single central structure. The five hoods, which some mistake for petals, are big nectar storage, drawing insects galore to the flower. Pollen occurs in pairs of gummy sacs that have to be precisely dragged out from a little enclosure by an insect leg, and transported to another flower of a different plant, and successfully inserted into one of 5 little slits that hide the stigmas of the female ovary. Since each pollen sac houses hundreds of little pollen grains, if it finds its way to the target, a pod full of seeds will result. You seldom see a milkweed pod only half packed, (as is often the case with cucumbers or ears of corn.) But the rate of pod formation is low, about 1 percent or so success, and that’s why a plant that produces hundreds of flowers in many bunches will only produce a few pods. Fellow ultra-nerds can further investigate the intimate details of the milkweed reproductive strategy here. Thrill as Craig Holdrege describes the travails of insects which lost legs or died in the process of obtaining nectar, and getting caught in the corolla structures of the milkweed. Whoever said that nature is a hard mistress was not kidding.

Milkweed pods swell and form rubbery bristles on the exterior as they develop. As they dry out, they crack open, revealing a hundred or more seeds, each attached to a tuft of silk. As these dry out, they take flight and increase the milkweed population everywhere. Silk from milkweed pods has been produced commercially to stuff pillows, insulated jackets, and even life jackets during war time. This fluffy stuff has great water resistance, and, a bit like dryer lint, can also be used to start fires. A little story from prior to the wide availability of the internet: Kids in flyover country used needle and thread to string milkweed seeds into necklaces. Before those kids are castigated for killing thousands of milkweed embryos, and endangering monarch butterflies, rest assured that milkweeds are perennial, and reproduce copiously by spreading rhizomes in the ground, as long as there’s enough sunlight. If you cut those volunteer shoots, more will pop up, asparagus-like.

Coming from the same family, Apocynaceae, Dogbane, a.k.a. Indian hemp, (Apocynum cannabinum) is often confused with milkweed. To distinguish it, pay attention to the solid, rather than hollow stem, narrower leaves, hairless leaf and stem, a white powdery substance which can be rubbed off of the stems, branching habit, and white flowers. It produces poisonous, cardenolide glycosides in higher concentrations, and is a bitter, do-not-eat. Some herbalists use it for heart failure, formerly described as dropsy. Don’t try dosing yourself at home unless you have lot of education regarding this weed and heart conditions. Similar cardenolide compounds exist within the milkweeds, but at low concentrations. That’s why milkweed is palatable, while dogbane is spit-it-out bitter. Survivalists regard mature dogbane plants to be a good source of long lasting, natural material for making cordage. Those preparing for when the SHTF have such things in mind as making nets and ropes from available natural fibers.

Forager and author, Samuel Thayer, theorized in The Forager’s Harvest that a case of misidentification accounts for long held misconceptions about poisons in milkweed. He wrote that famed forager, Euell Gibbons, likely confused dogbane and milkweed at some time, and attributed the bitterness of the former to the latter. (There are also some bitter milkweed species such as blunt leaf milkweed, A. amplexicaulis, in Northeast U.S. that could have added to confusion.) The habit of Euell Gibbons was to repeatedly boil milkweed to get rid of bitterness, but the common milkweed is not bitter. Most, but not all foragers boil (briefly and only once) the milkweed components such as buds, young flowers, shoots and top leaves, to avoid possible stomach upset that may come with consuming significant quantities. Some are more sensitive than others to the raw products.

The suggestion that common milkweed contained significant amounts of bitter toxic compounds sufficient to be poisonous to humans was slavishly and unquestioningly followed by 50 years of subsequent foraging and botanical authors. This has led to ….. more food for Samuel Thayer, you, and us!! That being said, you might wish to lean towards younger, less bug eaten specimens of A. syriaca when foraging, so that you can eat more of them. While the content of bitter cardenolide constituents is fairly low in our preferred species, it seems that the plants will produce more and/or different types of these compounds in response to attack by insect herbivores such as the monarch caterpillars. Not only that, the caterpillars tend to retain these molecules long term, causing themselves and their butterfly, adult forms to be less palatable, particularly to predators such as birds.

The top milkweed munchies, in order of various forager chef ratings of delectability are:

The immature pods an inch or less long

Shoots as they come out of the ground with 2 or 4 leaves on them

Flower buds shortly before they open

The white seeds and immature silk scooped from the inside of pods that are less than 2 inches long

Flower shortly after they open, and before they become droopy

Little leaves at the tops of the plants

All of these components can be blanched / boiled for a minute or two, then eaten, or further cooked whichever way you want.

Lastly for now, fresh milkweed latex has had long traditional uses for skin disorders. It seems to be anti-infective for the cuts and scrapes of outdoor life. Fresh latex also can be applied directly to warts, and will gradually eliminate them. This material has also been applied to ringworm skin infections. Naturally, there is little American interest in useful medicinal characteristics of this U.S. native plant to be found. Here and there some interest in the proteolytic enzymes present in the latex can be found in other countries. Some quinolines and other compounds found in our weed aroused interest in Nigeria for the potential against Plasmodial parasitic causes of malaria. We do know that if interest in milkweed for food or medicine grows, suddenly it will become abundantly available for our ever popular monarch butterflies.

Got a favorite weed? If and when it grows here, we can do it. Or else, you have to supply all the pictures, and take credit for them :-D Who would want to tell us about their favorite weed in a podcast? We have plans and dreams to drag our readers into this. :-D

Where We Dig

1. Apocynum androsaemifolium: INTRODUCTORY. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/forb/apoand/all.html

2. Salinas Ibáñez ÁG, Origone AL, Liggieri CS, Barberis SE, Vega AE. Asclepain cI, a proteolytic enzyme from Asclepias curassavica L., a south American plant, against Helicobacter pylori. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2022;13. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2022.961958

3. Asclepias syriaca (Common Milkweed) | North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants/asclepias-syriaca/

4. Asclepias syriaca | Bring Back The Monarchs. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://monarchwatch.org/bring-back-the-monarchs/milkweed/milkweed-profiles/asclepias-syriaca/

5. Asclepias syriaca. Common Silkweed. | Henriette’s Herbal Homepage. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://www.henriettes-herb.com/eclectic/king1854/asclepias-syri.html

6. Azeez T, Iwuji S, Chidiebere U, et al. Bioactive Constituents and Potency of Aqueous-Methanolic Extract of Asclepias syriaca on Plasmodium falciparum Infected Albino Rats. Journal of Biomimetics, Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering. 2021;51:15-28. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/JBBBE.51.15

7. Common Dogbane (Apocynum cannabinum). Accessed September 5, 2023. https://illinoiswildflowers.info/prairie/plantx/dogbanex.htm

8. Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca). bplant.org. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://bplant.org/plant/79

9. Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) – Project Food Forest. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://projectfoodforest.org/2016/08/16/common-milkweed-asclepias-syriaca/

10. Common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) | Identify that Plant. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://identifythatplant.com/common-milkweed-asclepias-syriaca/

11. Araya JJ, Kindscher K, Timmermann BN. Cytotoxic Cardiac Glycosides and Other Compounds from Asclepias syriaca. J Nat Prod. 2012;75(3):400-407. doi:10.1021/np2008076

12. How to Eat Common Milkweed Flowers. WildFed. Published July 7, 2020. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://www.wild-fed.com/blog/how-to-eat-common-milkweed-flowers

13. Hutchens AR. Indian Herbalogy of North America. Shambhala; Distributed in the United States by Random House; 1991. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL1567124M/Indian_herbalogy_of_North_America

14. Medicinal herbs: COMMON MILKWEED - Asclepias syriaca. Accessed September 6, 2023. http://naturalmedicinalherbs.net/herbs/a/asclepias-syriaca=common-milkweed.php

15. Milkweed Flower Morphology and Terminology. Orbis Environmental Consulting. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://orbisec.com/milkweed-flower-morphology-and-terminology/

16. Bergo A. Milkweed Shoots. Forager | Chef. Published June 13, 2014. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://foragerchef.com/milkweed-shoots/

17. Milkweed: Medicine of Monarchs and Humans. Milkweed: Medicine of Monarchs and Humans. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.herbalgram.org/resources/herbalgram/issues/101/table-of-contents/hg101-feat-monarchmilkweed/

18. Winnick T, Davis AR, Greenberg DM. PHYSICOCHEMICAL PROPERTIES OF THE PROTEOLYTIC ENZYME FROM THE LATEX OF THE MILKWEED, ASCLEPIAS SPECIOSA TORR. SOME COMPARISONS WITH OTHER PROTEASES. J Gen Physiol. 1940;23(3):301-308.

19. Abioye J, Manaja E, Olokun A. Phytochemical Properties and Proximate Composition of Asclepias syriacal. Asian Journal of Research in Crop Science. Published online January 18, 2022:30-34. doi:10.9734/ajrcs/2022/v7i130130

20. McCay S, Mahlberg P. Study of Antibacterial Activity and Bacteriology of Latex from Asclepias syriaca L. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1973;3(2):247-253.

21. Thayer S. The Forager’s Harvest - A Guide to Identifying, Harvesting, and Preparing Edible Wild Plants. Forager’s Harvest Press; 2006. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL8588402M/The_Forager's_Harvest

22. Nazar N, Goyder DJ, Clarkson JJ, Mahmood T, Chase MW. The taxonomy and systematics of Apocynaceae: where we stand in 2012. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 2013;171(3):482-490. doi:10.1111/boj.12005

23. Agrawal AA, Petschenka G, Bingham RA, Weber MG, Rasmann S. Toxic cardenolides: chemical ecology and coevolution of specialized plant–herbivore interactions. New Phytologist. 2012;194(1):28-45. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.04049.x

24. Züst T, Petschenka G, Hastings AP, Agrawal AA. Toxicity of Milkweed Leaves and Latex: Chromatographic Quantification Versus Biological Activity of Cardenolides in 16 Asclepias Species. J Chem Ecol. 2019;45(1):50-60. doi:10.1007/s10886-018-1040-3

Awww the Common milkweed! Love it!

Milkweeds are super abundant in my region! I eat the spring shoots of milkweed and use pleurisy root medicinally. In my next book, I'll have a recipe for milkweed shoot and harbinger of spring tuber casserole.... okay, I can't resist sharing... here it is:

Harbinger of Spring Casserole with mixed spring shoots.

Ingredients

Harbinger of spring tubers – 1/2-1 cup, or so

Asparagus and/or asparagus-like shoots of early spring vegetable (any you find int his book will work just fine) or fiddle head ferns, etc.

Early spring greens – either spinach or wild greens, chopped

Optional veggies for flavor – fresh, sweet peas, chopped carrots

Onion or other alliums, chopped fine

Celery

Mushrooms

Chopped nuts like pecan, hickory or almond (optional)

Chicken stock or broth

Flour and butter enough to make roux

Milk

Mayonnaise

Cheese

Bread crumbs

Herbs

½ glass white wine

Dash of Worcestershire sauce, hot sauce, etc. (optional)

Instructions

This is much like other casseroles I have mentioned, but we are really going to try to stretch the Harbinger of spring tubers out along with maybe a handful of milkweed shoots or some Solomon's seal. This is a basic recipe for any time you only have say, one side-dish sized amount of a wild vegetable but you either need to make more food from it for necessity or want to share it with multiple people. All of these ingredients are interchangeable, and if you don’t have something (other than the roux) substitute something else – you can use most anything from the garden, canned or frozen vegetables, etc.

Start by cooking the tubers, alliums, mushrooms and tougher veggies in some fat and salt. Once tender, toss in any leaf vegetables and allow them to wilt. When soft, either push them to the side or reserve them.

Add fat and flour and cook over medium heat, stirring until the flour is cooked

Stir in Broth, wine and milk

Add herbs, salt and pepper, Worcestershire, a grate of nutmeg, crushed red pepper, Creole Seasoning, etc…. Whatever you like

Taste and adjust seasonings

Add the nuts

Remove from heat

Stir in the mayo… maybe ½ cup

Pour into a casserole dish

cover the top with grated cheese and bread crumbs

Bake until brown and bubbly

I usually add leftover chicken to a casserole such as this. You could certainly include anything you like, from meat to fish, to boiled eggs. The herbs, seasonings and ingredients you use are entirely up to your taste. Casseroles are simple, humble, French home cooking and can be made with literally anything added to a cream soup base (roux and milk) and baked. This is an excellent way to use stale bread and cheese, various veggies, scraps of meat, leftover broth or stock, etc. Only a century ago, oysters and lobster were the food of the poor, and many such casseroles including foraged vegetables, stale bread, abundant milk and shellfish, etc. were staples of the diet both in America and Europe. Basically, I figure if it would taste good in a soup or an omelet, it will be even better in a casserole!